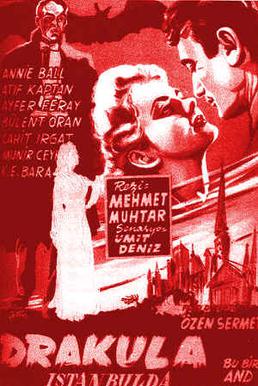

The publication of the Icelandic Dracula and how it has turned out to be an abridged version of the Swedish Dracula has received a lot of attention by Dracula scholars in the last five or so years, but another translation, the Turkish Dracula, is also a fascinating freely adapted version of Stoker’s masterpiece. While critics debate whether the Swedish Dracula may be based on an earlier version of Dracula or whether Stoker had some hand in producing it, Dracula in Istanbul, the translation published by Neon Harbor in 2017, is definitely a free adaptation that Stoker could not have been involved in since it was published in 1928. The translator, Ali Riza Seyfioglu, actually named the novel Kasigli Voyvoda, which translates as The Impaling Voivode. However, the translation back into English has been titled Dracula in Istanbul because the 1953 Turkish film based on the novel was given that name, in Turkish Drakula Istanbul’da. The film can be found on YouTube for those curious to watch it, though it is itself very freely adapted from Seyfioglu’s translation.

Dracula in Istanbul is a fascinating book largely because it is the first to equate Dracula with Vlad Tepes. The main characters are Turkish and instantly think of Dracula as the great warrior who fought against Mehmed II. Instead of Jonathan Harker traveling from London to visit Count Dracula, we have a lawyer named Azmi traveling from Istanbul to assist Dracula with purchasing property in that city. The other characters similarly have Turkish names. Dr. Afif and Dr. Resuhi are Dr. Seward and Van Helsing. Mina is named Guzin and Lucy becomes Sadan. Arthur Holmwood/Lord Godalming becomes Turan and Quincey Morris is Ozdemir. They are all Turkish, and the three suitors for Sadan’s hand are men who fought in the Turkish War for Independence.

Because Vlad Tepes, referred to simply as Dracula in the novel, is known to have been the enemy of the Turkish people from nearly five centuries before, Guzin and Azmi immediately think of the Count Dracula whom Azmi is going to visit as a possible descendant of the warrior voivode Dracula who wreaked havoc on the Turks and impaled his enemies. Little do they know he is the same person, or so the text seems to imply, although it is never explained to us how he could still be alive centuries later or how he became a vampire.

The plot follows closely that of Stoker’s novel despite the changes in character names and setting. The events in Dracula’s castle are largely the same, but the changes begin to be more significant after that. Almost more interesting than the changes Seyfioglu makes is what he chooses to omit since the book translated is a paperback of only 158 pages and that includes seven pages devoted to photos from the film version.

The first notable omissions are when Dracula travels to Istanbul. There are no scenes aboard the Demeter, no captain nor ship log, no wolf running upon the shore, nor no old men on shore telling the female main characters of the past. Almost immediately after the scenes in the castle, Sadan becomes ill and everyone is concerned for her. The scenes with Sadan follow the text closely up to her death and through the scenes of the men having to hunt down and kill her. But all references to Renfield and an insane asylum are omitted.

Also omitted are all the scenes with Dracula in them in London, save for when Azmi first spots him and notes he has grown younger. There is no scene where money falls from a bag Dracula holds, and most notably, no scene where the men break in while Jonathan is unconscious and Mina drinks blood from Dracula’s chest. Consequently, Guzin never becomes close to changing into a vampire, so the men make no oath to kill her if need be, and there is no hunt for Dracula where her second sight abilities are used to pursue him. One wonders if the Islamic readers would have found such scenes too sexual so they were omitted, or perhaps the novel was simply considered too long by Seyfioglu, so he trimmed out more than half the text.

Dracula does not try to return to Transylvania, so no pursuit of him takes place. Instead, the men simply hunt down his coffins in various places in Istanbul and then sanctify them so he cannot return to them, thus narrowing down the possibilities of where he can be until they can slay him in his coffin. This change is close to the play and cinema versions first made from Stoker’s novel.

One interesting addition to the novel is that there is no use of Christian symbols, other than a cross a peasant woman tries to give to Azmi when he first goes to the castle and is in Romania. Garlic is still used to protect Sadan, but instead of crucifixes or sacred communion hosts, pieces of paper with verses from the Quran are inserted in the coffins so Dracula cannot rest there. Such papers are also used to seal up holes in the walls of Sadan’s tomb so she cannot enter except through the main entrance so the men can capture her.

The end result for Dracula is the same. Turan slices off Dracula’s head while Ozdemir stabs him, but Ozdemir is not wounded and does not die. Dracula disintegrates almost immediately, but Guzin does not witness a look of peace come across his face as in Dracula. Finally, there is no epilogue, and no young Quincey Harker to represent hope for the future.

These changes do not take away from the power of the novel. It is just as gripping as Stoker’s original, even if abridged. It even in at least one sense tries to improve upon Stoker’s novel by stating that the men who give Sadan blood fortunately and by coincidence all have the same blood type, a necessary correction since blood types were not fully understood in Stoker’s day and the blood transfusions would have killed Lucy if the blood types had not matched.

To what extent Stoker intended Count Dracula to be representative of Vlad Tepes is something that has been debated now for decades. Consequently, Dracula in Istanbul is interesting because the Turkish people instantly knew the association, one that would have been known by few if any of Stoker’s original British Victorian readers.

Also of interest is that the translator, who is passing the novel off as his own work with no reference to Stoker, uses the Gothic device of a found manuscript by stating in the preface that the papers that make up the novel were found in a pile as if they rained down from the sky. He found them wrapped in newspapers when getting off of a ferry and could not find their owner, but they clearly represent the journals of men and women that were arranged in a specific order. He states that the book almost reads like a novel, but he wonders if it can be true or not. I do not know if the found manuscript device is common in Turkish literature, but if not, it suggests Seyfioglu was knowledgeable of European Gothic literary traditions to use it. At the same time, he must have banked on the fact that his countrymen were not familiar with such traditions since he published the novel under his name with no credit to Stoker.

Dracula in Istanbul, with a foreword by Kim Newman and an afterword by Iain Robert Smith, is a fascinating addition to Dracula scholarship and helps us broaden our understanding of how literary characters from one culture are adapted by other cultures. In fact, Seyfioglu also translated Edgar Rice Burroughs’ The Beasts of Tarzan to similar effect, and as Smith notes, Count Dracula has become a worldwide figure, even fighting Batman in a Filipino film and a resurrected Bruce Lee in a Hong Kong film. Each culture has seen fit to adapt him to their own needs. Anyone interested in Dracula and the development of the vampire in literature and film would do well to read Dracula in Istanbul.

_________________________________________

Tyler Tichelaar, PhD, is the author of King Arthur’s Children: A Study in Fiction and Tradition, The Gothic Wanderer: From Transgression to Redemption, The Children of Arthur historical fantasy series, Haunted Marquette: Ghost Stories from the Queen City, and many other titles. Visit Tyler at www.GothicWanderer.com, www.ChildrenofArthur.com, and www.MarquetteFiction.com.