George W. M. Reynolds (1814-1897) needs no introduction to regular readers of this blog. I have written about numerous of his works here, especially his Gothic novels, but even his non-Gothic works contain elements closely associated with the Gothic. Reynolds was also an author who had no qualms about capitalizing upon the works of other authors, from his sequel to Dickens’ The Pickwick Papers, titled Pickwick Abroad, to his borrowing of Eugene Sue’s The Mysteries of Paris to create the Victorian bestseller The Mysteries of London.

In Robert Macaire; or, The French Bandit in England (1839), Reynolds again recycles someone else’s work to create his own. I had never heard of the character of Robert Macaire before reading this novel, but according to Wikipedia, he was a stock character in French literature for about sixteen years before Reynolds borrowed him and sent him across the channel. The Wikipedia entry on the character states:

“Robert Macaire is a fictional character, an unscrupulous swindler, who appears in a number of French plays, films, and other works of art. In French culture he represents an archetypal villain. He was principally the creation of an actor, Frédérick Lemaître, who took the stock figure of ‘a ragged tramp, a common thief with tattered frock coat patched pants’ and transformed him during his performances into ‘the dapper confidence man, the financial schemer, the juggler of joint-stock companies’ that could serve to lampoon financial speculation and government corruption.

“Playwright Benjamin Antier (1787–1870), with two collaborators Saint-Amand and Polyanthe, created the character Robert Macaire in the play l’Auberge des Adrets, a serious-minded melodrama. After the work’s failure at its 1823 premiere, Frédérick Lemaître played the role as a comic figure instead. Violating all the conventions of its genre, it became a comic success and ran for a hundred performances. The transformation violated social standards that demanded crime be treated with seriousness and expected criminals to be punished appropriately. The play was soon banned, and representations of the character of Macaire were banned time and again until the 1880s. Lemaître used the character again in a sequel he co-authored titled Robert Macaire, first presented in 1835.”

The next mention of Macaire at Wikipedia is to Reynolds’ novel, and while Macaire would appear in numerous other works, including a 1907 film, what interests us is only his early depictions that inspired Reynolds. That depiction also includes Bertrand, his good friend, who often accompanies him. While the plot is more complicated than I will get into here, I will hit the highlights that make the novel interesting in relation to Reynolds’ other works.

In Reynolds’ novel, Macaire and Bertrand leave France for England, first robbing the Dover mail coach and tying up passenger, Charles Stanmore, who will figure later in the plot. They then obtain a letter from a business in Paris that says a M. Lebeau will be going to see Mr. Pocklington in England to transact business and asks that Pocklington advance money as needed to Lebeau. Macaire decides to pretend he is Lebeau and under that guise introduces himself to Pocklington, soon finding himself staying under Pocklington’s roof with his friend who goes by the name of Count Bertrand. Mr. Pocklington has a wife, and more importantly, a niece, Maria. Although Macaire is about forty and Maria closer to twenty, he soon wins her love. All the while, he is also receiving financial advances from her uncle under the belief they are connected to business.

Not surprisingly, Macaire seduces Maria, but not before making her vow to love him no matter who he truly is. The scene recalls those in Gothic novels like Melmoth the Wanderer, where a woman basically sells her soul to her lover. Maria makes the vow, and then Macaire reveals his true identity as a bandit.

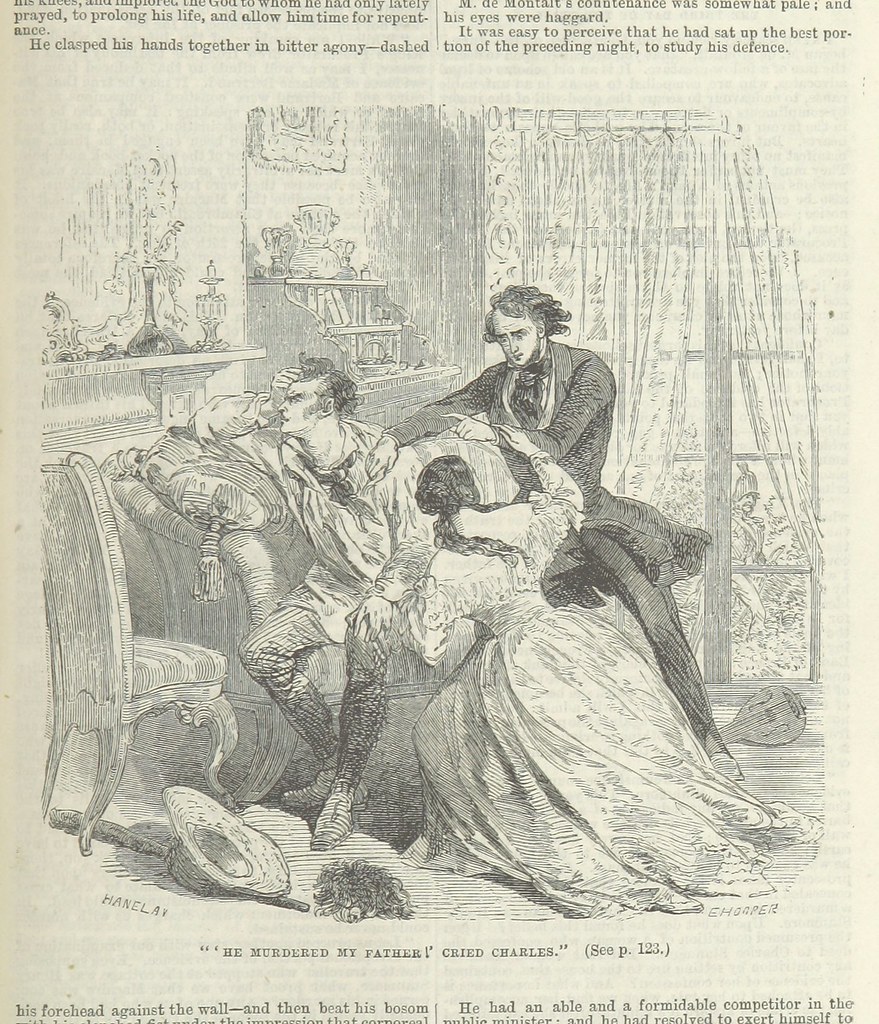

Stanmore, the victim at the mail coach, is not only a friend of the Pocklingtons but romantically interested in Maria, and while she is not interested in him, he becomes jealous of Macaire, not at first recognizing him as his assailant. As the plot unravels with Macaire returning to France and Stanmore also traveling there, Stanmore not only realizes who Macaire is, but he discovers Macaire was responsible for previously murdering his father. Macaire, meanwhile, visits a cottage where a young girl, Blanche, has been placed in the care of a couple, Paul and Marguerite, who were involved in the murder of Stanmore’s father. Blanche knows nothing of her family other than that her mother was the daughter of a nobleman and her father was disliked by the family. It turns out Blanche is the granddaughter of a count who has entrusted her to Macaire’s care. Macaire goes with Blanche to a notary to discuss the terms of money her grandfather wishes to settle on her, but when the grandfather visits at the same time, he and his granddaughter are reconciled, which infuriates Macaire, who wishes to have control of Blanche’s money.

Meanwhile, Maria’s friends and family realize who Macaire is. When he returns for the wedding, it is interrupted by Stanmore, who declares Macaire’s identity and accuses him of murdering his father. Maria tries repeatedly, even by eloping, to be with Macaire because of the vow she made him, and also because she is pregnant with his child, but her hopes are useless. In the end, she becomes ill. Macaire visits her on her deathbed, when she implores him to vow to reform. Heartbroken when she dies, she having been the only person who ever truly loved him, Macaire decides he will reform.

However, by now Stanmore has helped collect evidence against Macaire, which results in his capture and arrest by the police. Macaire hopes to be released so he can spend the rest of his life in penance, but following a trial, he is found guilty of murder and sentenced to decapitation. Fortunately, one of his criminal friends helps him to escape.

By this point, Stanmore has met and fallen in love with Macaire’s former ward, Blanche. Macaire, unaware of the marriage, has his heart now set on finding Blanche and convincing her to spend the rest of her days with him. When he goes to her house, she is horrified, for only now does she realize he is the convicted man her husband has sought to prosecute. Macaire implores her to have mercy on him and not turn him over to the police. He then makes the shocking announcement that he is her true father. She is instantly overwhelmed with happiness to know her father and also in fear of her husband’s wrath. When Stanmore returns home, his anger at seeing Macaire knows no restraint and he wishes to arrest or even kill him, declaring that Macaire murdered his own father, but then Blanche reveals that Macaire is her father. At this stunning revelation, Stanmore instantly relents and agrees to let Macaire escape, even lying and trying to postpone the police from pursuing him.

In the end, Macaire escapes and goes to Switzerland where he lives another six years in solitude, an “outcast” doing penance until he dies. Although the novel does not contain Gothic elements, his being an outcast, a Gothic wanderer really, and the guilt he feels for his past transgressions make him cousin to repentful Gothic characters like William Godwin’s St. Leon and James Malcolm Rymer’s Varney the Vampire. Macaire is actually one of the few in early Gothic novels who is not punished but allowed to find redemption through years of penance.

I suspect the novel was highly influenced by French drama, of which I know little. While coincidences and shocking revelations are not uncommon in Gothic literature and even the works of Dickens, I sense an influence here of French dramatists like Victor Hugo where the final scene is intended both to shock the reader/viewer and create deep emotion. Certainly, the dramatic revelation that Macaire is Blanche’s father and how this news immediately softens Stanmore’s heart has a similar shocking but almost cathartic effect on the reader. I felt the same grief and shock as when at the end of the opera Rigoletto, based on a play by Hugo, the father discovers that the sack he carries contains the corpse of his daughter.

Some other points of interest in the novel include when Macaire first returns to France, he goes to visit his fellow criminals. He enters the den of thieves and must give a password to get in, reminscent of secret societies, which often figure in Gothic novels. The author refers to the appearances of some of the criminals as being like Guy Fawkes, Cagliostro, and an insolvent priest. Cagliostro, notably, would be the alias of Joseph Balsamo, a historical magician or occultist of sorts who figures in Alexander Dumas’ Marie Antoinette novels of the 1850s.

Also notable is some of Reynolds’ social satire, which is often far from subtle. For example, in Chapter 37, Macaire escapes from the Pocklingtons by going down the neighbor’s chimney. The neighbor is a parson. When Macaire tells him the Catholics next door are saying mass and have tried to kill him, the parson declares “Catholics! What—are they Catholics?…if so, they are capable of anything.” He then gives Macaire some parson’s clothes to disguise himself. When Macaire then walks down the street dressed like a parson, we are told “the beggars in the street forebore to ask him for alms—because mendicants never do apply for charity to a clergyman, knowing very well that if they do, they will only be sent to the cage or the county gaol as rogues and vagabonds.”

Also of interest is that when Macaire is in prison, he meets a fellow prisoner who is executed for parricide or matricide, the jailor can’t remember which. (Reynolds had previously written in 1835 The Youthful Impostor, which he later revised and published as The Parricide, or The Youth’s Career of Crime. I have not yet been able to read this work, but one wonders if it is an intertextual play on his earlier work.)

Robert Macaire, besides its Gothic connections, is an interesting addition to the Newgate novels of the time. I feel Reynolds’ novel superior in pacing and plot to similar novels of the time such as William Harrison Ainsworth’s Jack Sheppard (serialized in 1839-1840) and Bulwer-Lytton’s Paul Clifford (1830). Paul Clifford may actually be another source for Robert Macaire since in that novel, Clifford is revealed to be the son of the judge who condemns him to death, similar to the fatherhood shock at the end of Robert Macaire. However, interestingly, and despite the controversy that the Newgate novels caused, Reynolds has no qualms with letting his criminal live—provided he is reformed of course. Plus, we should note that in the French version, as stated by Wikipedia above, Robert Macaire is also not punished, which caused outrage at the time. Certainly, the overlaps between the Gothic and crime novels are many, as would be evidenced later by Reynolds’ masterpiece, The Mysteries of London, a criminal and a Gothic transgressor being often the same kind of person, just one being surrounded by more Gothic atmosphere.

It is worth mentioning that Robert Macaire includes eighteen illustrations by Henry Anelay, which are exquisitely done. I could find little about Anelay online, though he illustrated many novels in his day. The pictures really add to the text, although I did not like that they were often ten or twenty pages before the action they depicted, which gave away the plot a bit at times.

I read the British Library edition of the novel, which is basically a photocopy of the original. The print is extremely small and I fear I will end up going blind one of these days from reading their books, but they are often the only editions of Reynolds’ works available. As always, I hope my blog posts will help bring Reynolds to greater attention so better editions will be issued and his popularity will grow so he can take his place among the great Victorian novelists, alongside Dickens, Trollope, Bulwer-Lytton, Ainsworth, and the Brontes. While his style may not be as ornate and his plots as deep or philosophical, his social satire and the way he writes gripping plots make Reynolds worthy of far more attention than he has received.

_________________________________________

Tyler Tichelaar, PhD, is the author of King Arthur’s Children: A Study in Fiction and Tradition, The Gothic Wanderer: From Transgression to Redemption, The Children of Arthur novel series, Haunted Marquette: Ghost Stories from the Queen City, and many other titles. Visit Tyler at www.GothicWanderer.com, www.ChildrenofArthur.com, and www.MarquetteFiction.com.