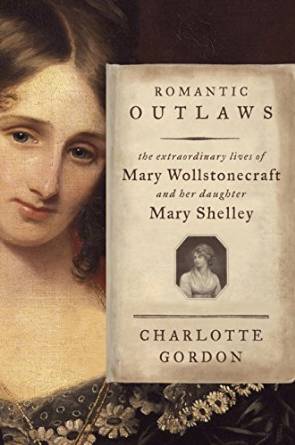

Charlotte Gordon’s new biography, Romantic Outlaws: The Extraordinary Lives of Mary Wollstonecraft and Her Daughter Mary Shelley provides a fascinating look into the lives of these two remarkable, though often misunderstood and maligned, women who were groundbreaking writers of the Romantic and ultimately the Feminist movements. The book is newly published this year by Random House, and while much of what it contains is the same biographical information provided in other books, Gordon has provided much more powerful connections between this mother and daughter by discussing them both in the same book.

“Romantic Outlaws,” a new biography, uses alternating chapters to explore the lives of Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Shelley and the mother’s influence on her daughter.

I decided to read this book because while I have studied and written about Mary Shelley, most notably her novels Frankenstein and The Last Man, and also about her father William Godwin’s novel St. Leon, in my own book The Gothic Wanderer. I have also read Shelley’s other novels—Valperga, Mathilde, Lodore, and Perkin Warbeck (I have yet to read Falkland)—and I wanted a better sense of how her life influenced those novels, especially after finding some comments about how her husband Percy Shelley influenced her depiction of Perkin Warbeck, the pretender to the throne, believed to have been Richard, Duke of York, one of the princes in the tower. I knew a lot about Mary Shelley’s biography but I had never sat down and read a full biography all the way through, and I wanted more insight into her life especially after the well-known years she was married to Percy Shelley, since the bulk of her writing occurred after his death.

So I intended to buy a biography of Mary Shelley, but then I stumbled on this book which also discussed her mother, whom I felt I really didn’t know much about. I knew Wollstonecraft had written some famous treatises and a couple of novels and of her affairs with Gilbert Imlay and Fuseli, but I was intrigued by the idea that she had a huge influence, despite being dead, on Mary Shelley’s life, and I thought it would be interesting to understand that influence better.

Romantic Outlaws is divided into alternating chapters about Wollstonecraft’s life and then Mary Shelley’s life. To some extent, Gordon has done this to tie together similarities and influences from mother to daughter, and that is apparent in a few places, but in others, less so. I have mixed feelings about this structure. Some other reviewers have complained that they had just get interested in one woman when the story flipped to the other woman. That is true, and at times, I got so caught up reading about Mary Shelley that when the chapter changed to be about Mary Wollstonecraft, I momentarily was confused which “Mary” was being referred to, but I quickly realized my mistake. It is possible the book would feel more organized if the book were divided in half, as two books in one, the first about Wollstonecraft, the second about Mary Shelley, but perhaps readers would ignore half then and only read the other half. Gordon made a decision to organize the book in this way, and despite its faults, it does have some advantages and did help to make the influence of Wollstonecraft on her daughter, as well as on Mary’s stepsister and half-sister and Percy Shelley, much more clear. I don’t think I would have ended up understanding Mary Shelley as well without having read so extensively about Wollstonecraft, and I think Gordon really showed that influence in a more complete way than any of the other books I have previously read about Mary Shelley.

I did learn a lot more about Mary Shelley than I knew in terms of her relationships, but I also was disappointed in the later chapters about her. Once Percy Shelley drowns, Gordon quickly wraps up the last half of Shelley’s life in a few chapters, which I wish had been spread out more. For example, she makes one passing reference to Mary Shelley’s friendship with the Carlyles, but I would have liked to know more about that friendship. I was also hoping to learn a little about her friendship with Frances Trollope, mother to the novelist Anthony Trollope and a novelist in her own write, but Frances Trollope is not even mentioned. Perkin Warbeck is only mentioned in passing. There is a little analysis of the other novels, but not what they warrant, especially in the case of The Last Man, which is arguably, Mary Shelley’s masterpiece, although I do appreciate that Gordon refers to it as the single voice of protest against war and manifest destiny in this time period. I suspect part of why these later years are brushed over is because Wollstonecraft’s life did not provide enough detail to provide more alternating chapters to juxtapose with Shelley’s, or maybe Shelley’s life was simply not as fascinating once her husband died, and Gordon was more interested in events than literary analysis. In any case, I was disappointed that I did not get out of this book what I initially wanted.

Mary Wollstonecraft was a novelist with a revolutionary pen who fought for the rights of women and left a tremendous legacy that would ultimately fuel the modern feminist movement.

That said, I got a lot that I did not expect in regards to Mary Shelley. I especially appreciated the discussions of Frankenstein and its composition. Gordon makes clear that while Percy Shelley did do some editing of Frankenstein, it is less than the editing done to many famous books, such as The Great Gatsby, and furthermore, the 1831 edition of Frankenstein was heavily rewritten by Mary Shelley, years after Percy Shelley’s death, and made to be much darker in tone. Charges that Percy Shelley was the genius behind Frankenstein have hopefully now finally been laid to rest. I have always thought it ridiculous he should get so much credit anyway since his own novels, Zastrozzi and St. Irvyne, while written before he was twenty, are far inferior to Mary Shelley’s first novel, which she wrote at about the same age. Percy Shelley was no great fiction writer and even his poetry I have usually found tedious with a few exceptions. Furthermore, as Gordon makes clear, Mary grew up in a very literary home and would have inherited her parents’ talent and have developed writing skills early from all the reading she did and her father’s influence. She knew her mother’s writings well and this no doubt developed her literary skills. I suspect had Percy Shelley never entered the picture, she would have been a writer regardless given her family background, and while Gordon doesn’t mention it, Mary’s half-brother, William Godwin, Jr. (another person I wish Gordon had spent more time on) wrote a novel also. They were a literary family, regardless of Percy Shelley being involved with them.

But the most valuable part of this book is the treatment of Mary Wollstonecraft. I grew to have so much respect for her. Yes, perhaps she acted like a stalker in her pursuit of Fuseli, but she also was a true revolutionary, trying to create a new world for women. Whatever faults she had I think we can dismiss as being the result of the confines of her time and the strain she experienced in going against the grain of her society. As Gordon says in the book’s conclusion of both women, “They asserted their right to determine their own destinies, starting a revolution that has yet to end.” I will not go into details here about how they did this, but will instead encourage people to read the book.

Finally, what I found fascinating about Gordon’s book was her treatment of how literary legacies are fought over. She discusses Godwin’s biography of Wollstonecraft, his desire to publish a biography before anyone else, and the harm it did to his wife’s reputation, despite his intending otherwise. Gordon also makes passing reference to how women who might be inspired by Wollstonecraft’s ideas were treated in the literature of the time, notably Harriet Freake in Maria Edgeworth’s Belinda (1801) and Elinor Joddrel in Fanny Burney’s The Wanderer (1814). That said, both of those characters, while meeting bad ends, have been read by modern literary scholars less as a condemnation of Wollstonecraft’s ideals and more as a subversive statement of how women were treated—a point Gordon overlooks. I wish again that more literary analysis had been included in this case, especially since The Wanderer is a feminist masterpiece in my opinion, as I discuss in more detail in my book The Gothic Wanderer, and I would have liked more comparison between Wollstonecraft and Burney, who was arguably the greatest female novelist of the late eighteenth century and very much a woman who used her novels to champion women, even if in more subtle ways—yet, while Gordon never directly says so, when she cites the female novels of the day that Wollstonecraft disapproved of, it often sounded like she was referring to plots found in Burney’s novels.

Mary Shelley also had to fight to preserve her husband’s literary legacy, and in many ways, she chose to whitewash it to remove the scandal and atheism Percy Shelley was known for. Similarly, Gordon explores how Mary Shelley’s own literary legacy has changed over the years. Ultimately, both of her subjects were rediscovered in the 1970s and today have been given their place in the canon of British literature, a place well-deserved.

Mary Shelley, too often in her husband’s shadow, was devoted to preserving and cultivating the Romantic legacy. Today, she is acknowledged as one of the greatest Romantic writers.

Personally, I found Romantic Outlaws to be a valuable and eye-opening book. It adds to and expands on the conversation about these two fascinating women, and it leaves room for further exploration. I will definitely be reading Wollstonecraft’s novels now, and Romantic Outlaws also made me want to read more of Godwin’s work. In truth, I found the book hard to put down, and while I wish it had even more information about these women, at 547 pages of primary text, it is a good length and reads with excellent pacing. Both informative and entertaining, Romantic Outlaws is literary biography made to read almost like a novel (in a few places early in the book I felt like Gordon bordered on fiction in presenting viewpoints of the subjects in the book, something she’s been charged with in her biography Mistress Bradstreet). My criticisms of this book are minor really when placed aside the tremendous amount of research and the vivacity of the presentation throughout that Gordon has accomplished. I was won over by Gordon’s style, and since I am a fan of Anne Bradstreet (and relative), I will be interested in reading that Gordon biography in the near future. Most importantly, Gordon has achieved what she set out to accomplish—to convince her readers of the powerful voices these two women had and to help us better understand them and their time.

___________________________________________________

Tyler Tichelaar, Ph.D., is the author of King Arthur’s Children: A Study in Fiction and Tradition, The Gothic Wanderer: From Transgression to Redemption, and The Children of Arthur novel series. Visit Tyler at www.ChildrenofArthur.com and www.GothicWanderer.com