It is difficult to say which of George du Maurier’s three novels, Peter Ibbetson (1891), Trilby (1894), or The Martian (1897), is the most intriguing and surprising. No one reads any of them any longer, and their author lives in his granddaughter Daphne du Maurier’s shadow, but all three novels are fascinating and really “mind-blowing” especially because they are all about the power of the mind. Peter Ibbetson was made into a 1935 film starring Jackie Cooper (well worth watching) and an opera, and Trilby became a famous play and introduced the trilby hat and the term “Svengali” into the language as well as influencing countless other works including The Phantom of the Opera. But The Martian never received any such fame. The title suggests it’s a science fiction novel, and given its publication date, one expects it to be along the lines of H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds, but it is much closer to the themes of du Maurier’s earlier novels, with its depiction of the bohemian lifestyle and English-French culture (in fact, there is far too much French in it, at least for me, who has forgotten most of my French) and its issues of mind-control, while the science fiction elements are fairly minor, even though the story revolves around them.

I hesitate to describe The Martian as even being science fiction. It feels more like it is Gothic to me because of its supernatural theme. Yes, there is a Martian, but overall, it’s a realistic novel with a little Gothic burst of energy to it—not Gothic in the sense of it being at all scary—but simply having a supernatural bent to it. Of course, it is also a novel masquerading as a biography.

The Martian is narrated by Robert Maurice, who is the lifelong friend of the late Barty Josselin, presumed to be the greatest literary genius of the nineteenth century, and Maurice is going to reveal to us “the strange secret of that genius.” Literary critics have complained that the novel wanders about, is full of digressions, and is only valuable for its depiction of “la vie de bohême.” Little critical attention has been paid to the novel’s supernatural elements, and when it is, it is often misinterpreted. For example, Wikipedia quotes a passage from the novel saying that it refers to Swedenborg, but there is no reference in the entire book to Swedenborg, and the passage quoted actually refers to Barty. Whether or not Swedenborg’s theories had any influence on the novel, I do not know, although it seems possible, but such broad comments should not be made out of context.

The novel traces the friendship of Maurice and Barty throughout their years at a boy’s school in France and into their early adulthood as Barty tries to become a painter. Barty is remarkable throughout his youth for a certain charisma he has, as well as enhanced senses of sight, smell, etc. and a strange ability always to know in which direction north lies. At one point in their youth, Maurice asks Barty whether he has a “special friend above” but Barty only tells him that if he asks no questions, he will hear no lies. It is not until nearly halfway through the novel that these strange abilities of Barty’s are explained. I refer to the novel as Gothic largely because these enhanced senses are typically those that characters such as vampires or other supernatural characters would have, but how Barty acquired these abilities is where the novel crosses genre lines.

When Barty begins to lose his eyesight, he contemplates suicide, but then he wakes one day to find a letter beside his bed that he physically wrote while sleeping but which claims to be from a being named Martia. Martia says she (her sex isn’t clear at first) has inhabited many human and animal life forms before deciding that Barty was her favorite and she would inhabit him, which she has done since his childhood. She can do little to help him but is devoted to him and gives him his advanced sensory powers. As time goes on, Barty learns Martia’s entire story. Martia has gone through countless incarnations on Mars from the lowest to highest forms of life, but she only remembers her last incarnation as a woman. Barty has often remembered having dreams of being around mermaid-like people, and now he understands that is because Martians are amphibious. In time, Martia came to earth in a shower of shooting stars and after spending a century inhabiting various people and animals, she decided to remain in Barty.

In time, Martia’s spirit inhabiting him allows Barty to become a famous writer. He basically channels her spirit and writes while he’s in a sleeping state, which his wife observes. For me, the most disturbing part of the book is what he writes about. Why he is such a popular writer is fairly obscure in the novel, but at one point, Maurice tells us that Barty’s books were at first condemned by religions, but now are preached from pulpits because they confirm the “indestructible gem of immortality” in us and are the “golden bridge in the middle of which science and faith can shake hands.” They also are in favor of suicide as a normal way out of our troubles, and Maurice, while he won’t discuss the morality of this statement, does say that the cruelties of the world are ending because of Barty’s books. What is most disturbing is that because of the information in Barty’s books, which seem to advocate eugenics (although du Maurier doesn’t use the term), the human race is now four to six inches taller and its strength and beauty are increasing; however, his theories also advocate a sort of survival of the fittest to the point where those who are not beautiful or strong see the wisdom of not marrying and passing on bad genes to future generations. The narrator himself has decided not to have children so he doesn’t pass on his long upper lip and the kink in his noise.

Barty’s literary abilities clearly result from Martia’s influence, but they make Barty feel like a fraud. However, Maurice states that Martia simply gave him ideas that are the “mere skeleton of his work” while all the beauty and grace of the works are his own. In this passage, Martia is also describes as “his demon,” which seems an odd word choice since Martia is clearly benevolent, but “demon” at times refers simply to a wise supernatural being, as is the case in Bulwer-Lytton’s Gothic Rosicrucian novel Zanoni (1842).

As time goes by, Martia decides no longer to reside in Barty but to reincarnate herself as his child. The novel then treats of her childhood before she falls out of a tree and ends up dying at age seventeen, and Barty dies when she dies. It’s a rather anticlimactic ending, actually.

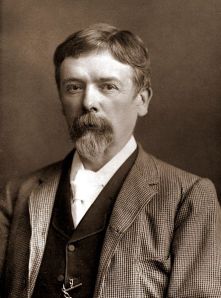

George du Maurier was the grandfather of authors Angela du Maurier, Daphne du Maurier, and the five Davies boys who inspired J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan

The Martian is really lacking in a plot, and du Maurier seemed aware of this deficiency since he has Maurice continually remind us it’s an autobiography and even show concern that he is boring the reader with all the details he’s including. That said, the idea of a supernatural being, in this case a Martian, channeling one’s writing is really fascinating to me, although it wasn’t revolutionary as a plot theme. Mediums were popular throughout the last half of the nineteenth century, and Martia herself remarks that all the knocking on tables (at séances) is fake. Novels were also reputably being channeled during this period, including a continuation of Charles Dickens’ The Mystery of Edwin Drood in 1873 by Thomas James, a Vermont printer who claimed he had channeled Dickens to complete the novel. What feels more revolutionary to me is that it is not a ghost or spirit but a martian who is the source of the channeling; today, the idea of alien implants is common enough in science fiction, but it wasn’t in 1896. Where did du Maurier come up with such an idea, I wonder.

Martia is also a sort of protector or counselor to Barty—at one point she is upset with him for not marrying the woman he tells her too. This idea of a supernatural counselor is common in Gothic Rosicrucian novels such as Zanoni, as well as in the Duchess of Devonshire’s The Sylph (1779). I also wonder whether du Maurier is giving a nod to William Morris’ utopian science fiction novel News from Nowhere (1890) when Barty refers to himself as “Mr. Nobody from Nowhere,” a name he adopts because he is the illegitimate child of a lord, a position that does not allow him to take his father’s rightful name. Interestingly, this is a similar situation that Juliet in Fanny Burney’s The Wanderer (1814) experiences, and Burney continually used terms like “Nobody” in her novels. The “sylph” as a Rosicrucian guide is also used in Burney’s novel.) More research would need to be done on all these possible literary sources, but it is clear du Maurier is writing within the Gothic literary tradition.

One last interesting aspect of the novel is that du Maurier writes himself into the novel as a character, frequently dropping his name as one of Barty’s artist friends, and Maurice even includes in his narrative a letter from du Maurier, in which he arranges for du Maurier to illustrate The Martian. This is also quite a revolutionary, playful postmodern move and while it is common today for authors to write themselves into their books, I don’t know of any authors prior to du Maurier who did so.

Of course, du Maurier did illustrate the novel, and the illustrations for it can be found in various places on the Internet, including at: http://www.erbzine.com/mag27/2726a.html, a site devoted to Edgar Rice Burroughs, author of the Tarzan and Mars novels. The website owner raises the possibility, unconfirmed, that Burroughs may have read The Martian and it may have influenced his own Mars series. Considering Burroughs’ Mars novels are often concerned with the power of the mind and even brain transplants, I think it’s likely, and Burroughs was definitely interested in evolutionary theories, if not eugenics itself. More research would need to be done to confirm the connection, however, so perhaps people who know more about the history of science fiction than I do will enlighten me further.

The Martian is far deserving of more attention than it has received. It is a pleasant, leisurely read and worthwhile just for its depictions of nineteenth century France, but its supernatural elements truly make it a novel ahead of its time, just like du Maurier’s two better known novels.

________________________________________________________

Tyler Tichelaar, Ph.D. is the author of King Arthur’s Children: A Study in Fiction and Tradition, The Gothic Wanderer: From Transgression to Redemption, and the upcoming novel Arthur’s Legacy, The Children of Arthur: Book One. You can visit Tyler at www.ChildrenofArthur.com and www.GothicWanderer.com