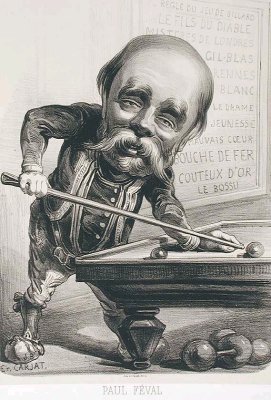

When I first heard about Paul Féval (1816-1887)—a writer of serialized French Gothic novels—technically, they are termed feuilletons—meaning serialized novels—who wrote about vampires some forty years before Bram Stoker and whose stories take place in or have characters from Eastern Europe, I was intrigued and wondered whether Stoker knew Féval’s work and was inspired by it in creating Dracula.

Whether or not Stoker ever read Féval is open to question and not something we can accurately determine. However, in this blog and my next one, I will look at the possibilities of an influence. There certainly was a great deal of influence among French and British novelists of the mid-nineteenth century. Féval properly belonged to a generation or even two before Stoker, but he was contemporary with another great British Gothic author, George W.M. Reynolds. Reynolds and Féval would be rivals of a sort in the literary world. After French author Eugene Sue came out with his The Mysteries of Paris (1842-3), Féval wrote an imitation in French he called The Mysteries of London (1843-4), which was published under the pseudonym Francis Trolopp—a play on the name of popular English novelist Frances Trollope (mother to novelist Anthony Trollope). Then Reynolds wrote a serial with the same title (1844-8), but in English. Féval apparently accused Reynolds of plagiarism and thought British authors were pirates ever after that (with no qualms, apparently, from how he had borrowed his own fellow French author’s idea). Obviously, French and British authors, therefore, were influencing one another.

Another example of this influence concerns Charles Dickens. I discovered in a collection of Charles Dickens’ letters that Dickens knew Féval. Dickens regularly corresponded with French actor Charles Fechter, and in a November 4, 1862 letter to Fechter, Dickens writes:

“Pray tell Paul Féval that I shall be charmed to know him, and that I shall feel the strongest interest in making his acquaintance. It almost puts me out of humour with Paris (and it takes a great deal to do that!) to think that I was not at home to prevail upon him to come with you, and be welcomed to Gad’s Hill; but either there or here, I hope to become his friend before this present old year is out. Pray tell him so.”

Later, in a letter to Fechter from February 4, 1863, Dickens again writes that he is in Paris and says, “Paul Féval was there, and I found him a capital fellow.” If only we could have known what was said at that meeting between two such illustrious authors.

How extensive Dickens and Féval’s relationship was is not known. Féval is not mentioned in either Ackroyd or Johnson’s biographies of Dickens, so it is doubtful they got to know each other well. Despite that, in the prologue to his novel Vampire City (published 1875 but believed to have been written about 1867 and therefore before Dickens’ death in 1870), Féval refers to Dickens as “My dear and excellent friend.” In this passage he is complaining about how English authors have pirated his works and he quotes Dickens for support on the matter, saying “Charles Dickens said to me one day, by way of apology: ‘I am not much better protected than you. When I go to London, if I happen to have an idea about my person, I lock my notecase, put it in my pocket and keep both hands upon it. It is stolen anyway.’” Were Dickens and Féval truly close friends or did Féval simply feel that quoting an English author would support his argument, especially Dickens who was widely known to have had his works pirated?

In any case, there clearly was an influence between French and British authors and they knew of each other’s works. However, Féval, because of the piracy, resisted having most of his works translated into English, although pirated versions happened, though I know of no evidence that his vampire novels were, but that does not mean Stoker might not have known of them. That said, according to Neil Miley in Henry Irving and Bastien-Lepage, Stoker spoke only broken French, but that doesn’t mean he couldn’t read it. I myself can read French far better than I can speak it, so it’s possible Stoker did read Féval’s vampire novels.

Féval would publish three vampire novels. The first, The Vampire Countess (1855 serialized; published in book form in 1865), will be the focus of the rest of this blog. The other two Knightshade (1860) and Vampire City (1874), I will discuss in my next blog where I will make some more comparisons between Stoker and Féval’s work. Fortunately for us, Black Coats Press (named for another of Féval’s novels) has reprinted these vampire texts with excellent introductions and afterwords by British author Brian Stableford. Stableford is extremely knowledgeable on the French serialized novels of the mid-nineteenth century and he writes extensively in these books about Féval’s place in his country’s literature alongside his contemporaries like Eugene Sue and Alexander Dumas (who would write a play The Vampire, the success of which may have led to Féval writing The Vampire Countess and whose novel Joseph Balsamo was inspired by English Gothic author Bulwer-Lytton’s Zanoni).

In Stableford’s afterword to The Vampire Countess, he goes into detail about all of the vampire novels published before it. I was surprised by how many of them there were—The Vampire Countess, Stableford says is probably the sixth full-length novel published. I was only aware of two prior to The Vampire Countess—John Polidori’s The Vampyre (1819) and James Malcolm Rymer’s serialized Varney the Vampire (1846-7) because my area of interest has been British Gothic. Apparently, the vampire was a popular topic on the Continent as well. According to Stableford, the first five would be:

Der Vampyr (1801) by Ignatz Ferdinand Arnold

Lord Ruthven, ou les Vampires (1820) by Cyprien Bérard

La Vampire, ou La Vierge de Hongrie (1825) by Etienne-Léon Lamothe-Langon.

Varney the Vampyre (1846-7) by James Malcolm Rymer

La Baronne Trépassée (The Late Baroness) (1853) by Pierre-Alexis Ponson du Terrail

Dr. John Polidori, whose story, The Vampire, was a major influence on vampire fiction in both England and France.

Stableford states that no known copy exists any longer of the first novel by Arnold. The second novel should probably be Polidori’s novel The Vampire, but Stableford omits it because it is not a lengthy work, more of a novella, while acknowledging its incredible influence on French Gothic literature. In fact, Bérard’s novel is definitely based on it since Polidori’s vampire was named Lord Ruthven (infamously modeled upon Lord Byron). Also noteworthy from this list is that Lamothe-Langon’s novel’s subtitle translates as The Virgin of Hungary, which shows that Eastern European characters and settings in vampire fiction long predate Stoker. In fact, a scholarly work on vampires to which Lamothe-Langon certainly had access was Dom Augustin Calmet’s treatise, Dissertations sur les Apparitions des Esprits, et sur les Vampires (The Vampires of Hungary and Neighboring Regions in English), first published in Paris in 1746, and reprinted several times. Like The Vampire Countess, Lamothe-Langon’s novel concerned Napoleon, so clearly Féval was influenced by it. In his introduction, Stableford also mentions Theophile Gautier’s novella La Morte Amoureuse (1836), which not only was known to Féval, but was also translated into English under the title Clarimonde, which further proves that French and British authors were reading and influencing each other across the channel.

But what of The Vampire Countess? Is it significant in our vampire journey toward Dracula? As I said, we have no indication that Stoker read it, but there is much in it that sets us up for Dracula.

Let me say here before discussing the novel’s plot that Féval is not always an easy author to read. The first of his novels I read was The Wandering Jew’s Daughter, a more or less comic novel making fun of the popularity of the Wandering Jew in the literature of the time. If there’s one thing I dislike in literature, it is the inability to take your subject seriously. A lack of sincerity, the blending of horror with comedy, is what has spoiled most modern horror films, and while Féval wasn’t the first to mock the Gothic tradition, he certainly didn’t improve on it when it came to the Wandering Jew tradition. Féval would also take the vampire legend less seriously in his later two vampire novels, but in The Vampire Countess, he is at least trying to be serious. There are comical elements to the novel, but a Gothic atmosphere is mostly retained and remains haunting throughout the story.

That said, the novel has some flaws from a lack of tight plotting—the fault of serialization—as well as because it is a sequel to an earlier novel, La Chambre des Amours (The Love Nest). Unfortunately, I don’t believe The Love Nest has been translated into English and Black Coats Press has reprinted The Vampire Countess without its prequel. The result is that it is difficult to make sense of many of the main characters and understand their relationships to one another since Féval assumes we know them when we read The Vampire Countess. Consequently, I found the novel confusing for quite a while, and like The Wandering Jew’s Daughter, I almost felt like I was reading a fragment of what could be a great book. Not until about a third of the way through this roughly 300-page book does the story become really fascinating.

I won’t go into all of the plot of The Vampire Countess, but just summarize the main points. Féval, as Stableford points out, can’t decide from the opening of the novel whether or not to take his vampire theme seriously. He talks of how vampires are being talked about in Paris, largely because of some bodies found in the Seine, but he also introduces the metaphor that Paris itself is the real vampire of the novel, sucking the life out of people, and suggesting it is not real vampires but simply crime in Paris that is the problem.

That said, the vampire countess is very real as a supernatural being, even if not quite the typical vampire. There is no bloodsucking in the novel, which is what vampires are defined by today. Instead, this vampiress is trying to retain her youth, which she can only do by tearing the scalps off young women and wearing them as if they are her own hair—that transforms her to be youthful again for a short time before she regains her old age. I suspect Féval knew of or drew on sources that knew of Elizabeth Bathory (1560-1614), the infamous Hungarian countess who liked to bathe in the blood of young virgins, believing that would help her to retain her youth. (That said, Elizabeth Bathory is not mentioned in Calmet’s work.)

Féval also makes his vampire very sexual. She masquerades as Countess Marcin de Gregory, but in truth, she is Addhema, a legendary vampiress who has a male vampire lover, Szandor. Szandor will only kiss her (Stableford points out that the French word used could mean more than kiss, maybe orgasm) if she brings him large sums of money. The final scene of the novel depicts them in the throes of their passion before Addhema kills her lover and herself by plunging a red hot iron through his heart and then hers—a murder-suicide. It is quite a sexual and disturbing scene, especially for a Victorian era novel.

There is much else about the Vampire Countess that is both confusing, not necessarily logical, and fascinating. While Addhema passes herself off in France as the Countess Marcin de Gregory, she also at one point claims to be Lila, whom she says is the countess’ sister. Lila seduces the main character Rene and tells him the story of Addhema. She does this because the vampiress cannot have a lover unless she first tells him the truth about her being a vampiress. Lila gets around this by telling Rene the story but not clarifying that she is the vampiress. Later, Rene dreams that Lila turns into the countess, but when he wakes, it’s not clear whether he was with Lila as the vampiress or not. This dream or hallucination of Rene’s is part of Féval’s intentional blending of reality and the supernatural to keep the reader and characters questioning whether vampires are real, as well as Féval’s own inability to be sincere about his vampire fiction.

The novel is set when Napoleon was First Consul, and Féval pulls Napoleon into the plot. One of the men the countess marries ends up accusing Napoleon of being her lover and challenging him—of course, Napoleon comes out on top here. Later, the countess claims Napoleon has given her a letter so military men will do her bidding. In truth, she has a forged document. She also appears to be plotting to overturn Napoleon and is in league with the Brotherhood of Virtue. None of these political activities are completely clear in the novel—least of all why the countess is politically motivated at all since it cannot serve her purpose to stay young or to achieve money to pay Szandor for the kisses she craves.

Altogether, The Vampire Countess is a strange novel, much of it feeling like filler that Féval wrote to fill his serial pages because he wasn’t sure yet where the plot was going. It is far from a perfect or even a truly powerful Gothic novel save perhaps for the final scene where Addhema plunges a red hot iron into Szandor’s heart—the scene reminds me of the passionate scenes in Anne Rice’s vampire novels. In my opinion, Féval lacked the intensity or sincerity of Eugene Sue or James Malcolm Rymer which kept him from being a first rate Gothic novelist. That said, The Vampire Countess is an interesting novel because of its historical place in vampire fiction and because it is the most serious of Féval’s vampire novels. Certainly, no one can deny that Féval holds a significant place in the Gothic and serialized literature of his day.

As for whether he influenced Stoker, more exploration is needed, and I will continue that quest in my next blog.

_____________________________________________

Tyler Tichelaar, Ph.D., is the author of The Children of Arthur series, beginning with Arthur’s Legacy and including Lilith’s Love which is largely a sequel to Dracula. His scholarly nonfiction works include King Arthur’s Children: A Study in Fiction and Tradition and The Gothic Wanderer: From Transgression to Redemption. You can learn more about him at www.GothicWanderer.com and www.ChildrenofArthur.com.