This year, Ivanhoe (1819), Sir Walter Scott’s most popular and perhaps greatest novel, celebrates its 200th anniversary. I first read Ivanhoe more than thirty years ago as a teenager. Since then, I have slowly been working my way through all his novels, but as my knowledge of literature has grown and especially my interest in the Gothic, I’ve always wanted to go back and reread Ivanhoe and recently did so. (I will not provide a summary of the novel here, but one can easily be found online; I am assuming readers are familiar with the novel.)

As a historical novelist myself, I revere Scott as the father of the historical novel—there were some historical fiction novelists before him, but he popularized the genre. As a lover of the Gothic, I also am well aware that Scott never wrote a truly Gothic novel, and yet, he sprinkles Gothic elements into many of them. I have long felt that he is the bridge between the Romantic or Gothic novel and realism in British literature. Of course, the novels of manners that preceded him—works by Jane Austen, Fanny Burney, and others—were largely realistic as well—but Scott does something special in Ivanhoe. He takes Gothic elements and removes the supernatural from them, making them real.

I do not know if Scott ever read Fanny Burney’s The Wanderer, or Female Difficulties (1814), although we know he met Burney, seeking out a meeting with her, so I suspect he did read it and was perhaps influenced by it in writing Ivanhoe. My reason for thinking so is that in the novel, Burney creates a character she refers to as “A Wandering Jewess.” The main character, Juliet, or Ellis as she is known throughout most of the novel, is not Jewish at all, but she wanders about England through a variety of difficult situations as she tries to earn a living, all the while unable to reveal her true identity. I won’t go into details about the novel, but an entire chapter of my book The Gothic Wanderer: From Transgression to Redemption is dedicated to Burney’s novel. It is sufficient here, I think, to say that Scott’s inspiration for creating his Jewess character, Rebecca, may have been inspired by Burney’s novel.

Scott was revolutionary in introducing a Jewish character into a novel in a sympathetic manner, although here again he was preempted by Maria Edgeworth’s Harrington (1817), written as a sympathetic portrait of Jews after a reader complained to Edgeworth about her anti-Semitic depictions of Jews in several of her previous novels. Scott was a fan and friend of Edgeworth and heavily influenced by her first regional novels, set in Ireland, in writing his own regional novels set in Scotland, so it wouldn’t be surprising if Harrington also influenced him in writing Ivanhoe. That said, Edgeworth’s novel is completely realistic. While Scott’s novel is also completely realistic, he sprinkles supernatural and Gothic images throughout it.

The Wandering Jew was a popular image in Gothic literature, as I discuss in depth in my book The Gothic Wanderer. Here, I will simply state that the Wandering Jew was cursed by Christ to wander the earth until His Second Coming. The Jew usually has hypnotizing eyes. He also has supernatural powers, such as being able to control the elements. He makes his first appearance in Gothic literature in Matthew Lewis’ The Monk (1795). Later versions of his character include Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner (1798), the vampire figure, and Rosicrucian characters who have the elixir of life that gives them immortality and the philosopher’s stone that can turn lead into gold, as in William Godwin’s St. Leon (1799).

Ivanhoe makes use of the Wandering Jew theme from the beginning. Ivanhoe is disguised as a pilgrim from the Holy Land who is wandering through the countryside when he meets up with the Jew, Isaac of York. Through the combination of these two characters, we have a Wandering Jew reference early on. Other Gothic elements borrowed here are that Isaac, as a usurer, is accused of “sucking the blood” of his victims to become fat as a spider—a vampire image, and a surprising one since the first vampire novel, The Vampire by John Polidori (1819), was not published until the same year as Ivanhoe, although vampire-type characters feature in several earlier Romantic poems, notably Coleridge’s “Christabel” (1816). Ivanhoe, in disguise, also has a mysterious origin since his identity is not known—this is typical of heroes in literature and especially supernatural beings, but also of Juliet in Burney’s The Wanderer.

Later, Scott reverses the Wandering Jew imagery when Front-de-Boeuf holds Isaac as his prisoner. We are told that Front-de-Boeuf fixes his eye on Isaac as if to paralyze him with his glance. Isaac’s fear also makes him unable to move.

Rebecca, Isaac’s daughter, has perhaps the most Wandering Jew characteristics. She is a healer, who has knowledge beyond most people. This knowledge makes people think she is a witch, ultimately leading to her nearly being burned at the stake, but she is more closely akin to the Rosicrucian Gothic Wanderer figures who have knowledge beyond most people. She says her secrets date back to the time of King Solomon, and when Ivanhoe is wounded, she says she can heal him in eight days when it would normally take thirty. Later, Rebecca also takes on the angst of a Gothic wanderer figure in the unrequited love she feels for Ivanhoe that cannot be restored. Many female characters of this period are also Gothic wanderers in their unrequited love, including Lady Olivia in Samuel Richardson’s Sir Charles Grandison (1753-4), Elinor in Burney’s The Wanderer (1814), and Joanna, Countess of Mar in Jane Porter’s The Scottish Chiefs (1809). Finally, Rebecca ends up before an inquisition and almost ends up being burnt for witchcraft. This scene reflects many Inquisition scenes in other Gothic novels, including Ann Radcliffe’s The Italian (1797) and the slightly later Melmoth the Wanderer (1820) by Charles Maturin.

Personally, I find Ulrica to be the most fascinating Gothic wanderer figure in the novel. She is a Saxon maiden who was forced to marry a Norman lord, and consequently, is filled with guilt and angst. She compares herself to the fiends in hell who may feel remorse but not repentance. When Ivanhoe’s father Cedric reminds her of what she was before her marriage and how the Normans have badly used her, she decides upon revenge via death. Ultimately, she burns down the castle and dies in the flames after mocking her husband. In fact, she mocks her husband by pretending to be supernatural. As he’s dying, Front-de-Boeuf hears an unearthly voice telling him to think on his sins, the worst of which was the murder of his father, a sin he thought hidden within his own breast.

Scott is also not above poking fun at the Gothic. Athelstane, heir to the Saxon kingdom that has been usurped by the Normans, ends up dying, only to be resurrected from the dead. This is a play both on Christ’s resurrection and the vampire figure. It is also a humorous moment in the novel. Other than being extremely strong, Athelstane has nothing heroic or supernatural about him but is a bit of an oaf more interested in filling his stomach than loving the Saxon heiress Rowena or regaining his ancestors’ crown.

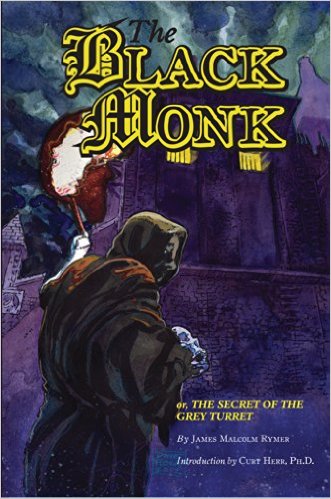

Frankly, I’ve always been a bit surprised that the novel is titled Ivanhoe since I don’t think Ivanhoe much of a hero, especially since for a good part of the novel, he is lying wounded. Ultimately, King Richard is the novel’s real hero. Like Ivanhoe, he is incognito in the beginning, disguised as the Black Knight, and he displays great physical strength. Ultimately, all the major acts of heroism fall to him. He frees the Saxon and Jewish characters, including Ivanhoe, when they are taken prisoner, and in the end, he saves England from the treachery of his brother, Prince John. Richard even heals the bad feelings of the Saxons toward the Normans, making Cedric and Athelstane relinquish their efforts to restore a Saxon king to the English throne. In my opinion, King Richard, as depicted in this novel, may be our first real superhero figure. A later novel, James Malcolm Rymer’s The Black Monk (1844-5), which is far more Gothic than Ivanhoe, would later also use him in a similar way where he returns to England incognito.

In the end, of course, Ivanhoe and Rowena marry, despite Rebecca’s love for him. Rebecca then visits Rowena to tell her she and her father are going to Granada where her father is in high favor with the king and where, presumably, as Jews, they will be safer. She says she cannot remain in England because it is a “land of war and blood” where Israel cannot “hope to rest during her wanderings.”

And so, in the end, Rebecca and her father embody the Wandering Jew figure, having to wander from England now to Granada, and who knows where they may wander again.

But ultimately, what is most remarkable about Scott’s novel is that the Wandering Jew figure in Gothic literature to this point did evoke some sympathy for the cursed man who must wander for eternity, and perhaps by extension, to the Jewish people. Scott, however, went a step further by creating realistic and sympathetic Jewish characters. For that reason, Ivanhoe is a bridge from the Gothic into realism, and beyond that, a step toward tolerance and humanity.

___________________________________________________

Tyler Tichelaar, PhD, is the author of King Arthur’s Children: A Study in Fiction and Tradition, The Gothic Wanderer: From Transgression to Redemption, The Children of Arthur novel series, Haunted Marquette: Ghost Stories from the Queen City, and numerous other books. Visit Tyler at www.ChildrenofArthur.com, www.GothicWanderer.com, and www.MarquetteFiction.com.