Charlotte and Emily Brontë were both concerned with what they believed to be the negative influences of the colonies on England. The colonies had made England a wealthy nation by increasing its trade prospects and providing a place for many Englishmen to make their fortunes outside their mother country; while the Brontë sisters appreciated the benefits England received from the colonies, they also feared the colonies would destroy England’s national identity and cause a moral decline among its people.

Wuthering Heights, Jane Eyre, and Villette, along with Charlotte and brother Branwell’s juvenile stories of Angria, all reflect the Brontës’ concern over England’s contact with the Other in the colonies. By establishing colonies, the English were oppressing other races, which the Brontës feared would result in rebellion against the conquerors and the eventual destruction of Britain. Also by oppressing other races, the English were becoming hardened to the point where they were now oppressing their own people, particularly their women. The Brontës feared Britain’s continued association with the colonies would eventually result in England turning savage like the foreign lands it sought to civilize. Charlotte and Emily Brontë both had their own ideas about how to deal with this situation; by chronologically looking at their works on the subject, it becomes apparent that each work responds to and builds on the work before it as if the two sisters were having a conversation about how to solve Britain’s colonial problems.

Bronte, Patrick Branwell; John Brown (1804-1855); Bronte Parsonage Museum; http://www.artuk.org/artworks/john-brown-18041855-20981

The Brontës’ interest in the colonies began when they were children and first beginning to write. In the late 1820s, Charlotte and Branwell Brontë began writing the legends of Angria, an imaginary kingdom founded by English colonizers on the West Coast of Africa. Angria may have derived its name from Kanhoji Angria, a man who established a pirate kingdom on India’s coast in the late seventeenth century. This kingdom resisted submission to the British government and its colonizers until 1756 when it was conquered by General Clive for the British Indian Empire (Gordon 29). That Charlotte and Branwell did not make up the name of Angria shows the Brontës’ knowledge of events in the colonies prior to and during their childhood. Their knowledge of the subject came from contemporary newspapers and Reverend J. Goldsmith’s A Grammar of General Geography, which Charlotte and Branwell used as a source for their stories in Africa (Ratchford 11). Possibly Charlotte and Branwell even decided to locate their Angrian colony near Fernando Po because in the 1820s, a writer for Blackwood Magazine had advocated it as a good place for British colonization (Meyer 247).

The legends of Angria also illustrate Charlotte Brontë’s familiarity with the British treatment of the natives. Charlotte probably named her main black character, Quashia Quamina, after a slave with a similar name who led a slave uprising in 1823 in British Guiana. Furthermore, the first name Quashia is derived from the racial epithet “Quashee” (Meyer 247). In the Angrian tales, Quashia resembles his namesake by also leading slave revolts against the English colonizers.

The Brontë children’s interest in Britain’s colonies was probably due to the excitement and dangers they imagined to exist in faraway lands. Azim remarks that for the Brontë children, the legends of Angria express “on one level, a feeling of anxiety and fear of the unknown and, on another, a feeling of triumph, based on a conquest of the Other” (112). However, conquest is not always easy. Charlotte, especially, seems to have been aware of the tension in establishing a colony, and she did not always side with Britain in its colonial problems. Although the Angrian stories always allow the English to conquer the natives, the natives often rebel under Quashia’s leadership. These continual uprisings represent the continual tension of colonial establishment, a tension mixing imperial triumph and the belief in Western superiority with a fear of the Other who at any time may rebel and destroy their conquerors.

Quashia Quamina is the pivotal character in understanding how fear of the Other works in the Angrian legends. Quashia is a child when his people’s land is invaded and conquered by the English. Most of his people, including his family, are murdered, while the rest are enslaved. However, the Duke of Wellington, leader of the new colony, decides to adopt the orphaned Quashia. Although by adopting the boy, Wellington may seem kind, his action displays a patriarchal attitude toward the natives, showing how the white race must take care of the black (Azim 131). For Quashia, adoption results in a traumatic displacement from his own people and cultural identity; when the English adopt him, they attempt to Anglicize him, which only causes future trouble for the colony (Azim 131).

As Quashia grows up, he realizes he is different from his adoptive family, which in turn leads to his realization that his adoptive family murdered his real family. Because of his native blood, Quashia can never be accepted as a white man; nor can he return to his own people since they are either deceased or living in subjection to their conquerors. His inability to determine his place in this new social order causes him frustration, and he begins to envy the power and culture of his conquerors, which he cannot possess (Azim 126-7). The natural result of his feelings is to rebel so he can end his and his people’s displacement, and gain his conqueror’s power to prevent such displacement from occurring again in the future (Azim 131-2).

As Quashia grows up, he realizes he is different from his adoptive family, which in turn leads to his realization that his adoptive family murdered his real family. Because of his native blood, Quashia can never be accepted as a white man; nor can he return to his own people since they are either deceased or living in subjection to their conquerors. His inability to determine his place in this new social order causes him frustration, and he begins to envy the power and culture of his conquerors, which he cannot possess (Azim 126-7). The natural result of his feelings is to rebel so he can end his and his people’s displacement, and gain his conqueror’s power to prevent such displacement from occurring again in the future (Azim 131-2).

Quashia leads several revolts in the Angrian tales, which reflect Charlotte Brontë’s concern for the mistreatment of the colonized natives. However, Charlotte could not bear the thought of English culture being utterly destroyed. In the Angrian stories, she always allows the English colonists to suppress rebellion. Charlotte’s youthful mind seeks an easy solution to the colonial problem, but in adulthood, the complexities of the issue would make her rethink the colonial situation.

The first Brontë novel to express a concern for Britain’s contact with the colonies is Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights. Little is known of Emily’s juvenilia, but it does not seem to be interested in the issue of the colonies or Britain’s contact with other cultures. However, Wuthering Heights is obviously dealing with the colonial issue, and the similarities between Heathcliff and Quashia in the Angrian tales are striking. Azim says of these similarities:

Thematic resemblances between Charlotte Brontë’s juvenilia and her sister’s only published novel do not necessarily signify a secret or undiscovered collaboration (as in the mysterious bed plays), but do suggest a fluidity of authorial collaboration which contradicts the static pairing according to contiguity in age upheld by most Brontë biographers (230).

Charlotte and Emily did not collaborate on the Angrian tales, but we know that in writing their novels, the Brontë sisters would discuss their ideas, so there is no reason to believe Emily would not have read her sister’s Angrian stories and have been directly influenced by them while writing her novel. Wuthering Heights is the beginning of Charlotte and Emily’s discussion together of how to solve Britain’s colonial problems.

The role Heathcliff plays in Wuthering Heights is almost the same role Quashia held in the Angrian tales. Heathcliff is the Other in the novel because he is not an Earnshaw or a Linton but an outsider. Nothing is known about Heathcliff’s origins except that Mr. Earnshaw finds him abandoned on the streets of Liverpool; the lack of knowledge about Heathcliff’s background leaves his racial origins open to possibility. Heathcliff’s first appearance in the novel portrays him as the Other by the savage terms the other characters use to describe him. Mr. Earnshaw says of him, “it’s as dark almost as if it came from the devil” (32), and Nelly remarks that Heathcliff is a “dirty, ragged, black-haired child” (32). Such statements have made some critics believe Heathcliff is possibly African (Azim 230, Heywood 194). That said, such arguments are rather a stretch given that Heathcliff is described in Chapter 3 holding a candle with “his face as white as the wall behind him.” In Chapter 4, after Hindley throws an iron weight a him, Heathcliff is “breathless and white,” and in Chapter 26, he is described as having blue eyes. Consequently, we cannot think him a pure-blooded African, but the possibility may exist if he is from the West Indies colonies that he is Creole.

If Heathcliff is of African origin, it would explain why Mr. Earnshaw uses “it” rather than “he” to refer to Heathcliff. Gender specific pronouns are usually used for humans while “it” is applied to animals. During the Victorian and colonial period, the English, to show their own racial superiority, often looked upon non-European races as being closer to animals than humans (Meyer 249). Charlotte Brontë will later use similar racial stereotypes in Jane Eyre.

If Heathcliff is partly African, then like Quashia, he has been adopted by the conquerors of his race; in fact, Emily Brontë probably based the Earnshaw family on the Sill family of Dent, whom she knew to have connections to the slave trade (Heywood 192). Again like Quashia, Heathcliff experiences displacement not only by being removed from his original home, but also because the Earnshaws try to make him one of them; they name him Heathcliff because it is the name of another Earnshaw child who has died (33); Heathcliff is expected by the Earnshaws to take on the identity of an English person rather than be himself.

However, as happened with Quashia, adopting and Anglicizing the Other into the conqueror’s culture results in failure. Mr. Earnshaw treats Heathcliff well, almost better than his own children, but upon Mr. Earnshaw’s death, Hindley demotes Heathcliff to a position resembling slavery. Heathcliff loves Catherine, but she will not marry him because he is not a gentleman; like Quashia, Heathcliff has been raised to be someone else, yet as an adult, he is not accepted by the culture he has been adopted into. Also like Quashia, Heathcliff now becomes envious of his conquerors and is determined to have revenge. He destroys the small community he is a part of by first coveting and then acquiring the property, daughter, and financial power of his adoptive home (Azim 230). The Earnshaws, by adopting Heathcliff, have only caused their own internal destruction.

Timothy Dalton’s portrayal of Heathcliff in the 1970 film of Wuthering Heights makes him look a bit like a vampire in this scene – interestingly, Dracula has also been read as a novel about immigration of foreigners into England.

Emily Brontë seems to have borrowed from Charlotte both a character and ideas and then used them to create her own novel. Charlotte’s juvenilia sees the solution to colonial problems as the conquest of the Other, even if such a conquest is cruel, because the continuation of British culture is more important. Emily Brontë’s solution in Wuthering Heights is similar, though not as simple. No one destroys Heathcliff in the novel; Heathcliff’s plans instead fail with the death of his son, Linton, and shortly after, Heathcliff also dies. Because Heathcliff leaves no living descendants, he cannot extend his revenge and power beyond the time of his death. The properties of Wuthering Heights and Thrushcross Grange now pass on to Hareton Earnshaw and Catherine Linton, descendants of the original landowning families, who also have pure English blood. The conclusion of Wuthering Heights appears to be a rejoicing that the Other no longer exists among these pure English people, and without the Other, the status quo is reestablished.

Emily Brontë’s decision to conclude Wuthering Heights by reestablishing the status quo and leaving no trace of Heathcliff’s influence is vital to understanding her solution to the colonial problem. Emily Brontë could have allowed Heathcliff to be accepted by the other characters as one of them, and consequently, he might have wed Catherine Earnshaw. However, an interracial marriage is something Emily knew her readers would not accept because it would mean Heathcliff and Catherine’s descendants would be racially impure. Although Heathcliff does marry Isabella Linton, his son nevertheless dies without issue to prevent the continuance of racial mixing. Since Britain would not accept the Other, Emily felt that Britain’s continued contact with the colonies would lead to Britain’s destruction. By Heathcliff’s death and the reestablishment of the status quo at the end of Wuthering Heights, Emily is showing the English that they must break off contact with the colonies. If they do not end contact, they will only be destroying themselves.

Emily Brontë’s solution appears to be a promotion of British isolation. Considering Emily’s own shy character and dislike of society, such a solution seems to reflect her personality. The solution may also reflect Emily’s own fear of the Other. She may well have never met an African person in her life, so consequently, the Other’s unfamiliarity would have made it fearful to her.

Charlotte Brontë was more outgoing than her sister; she also knew Emily’s solution was unrealistic; England could not cut itself off from the colonies because the British economy was now dependent on them. Although Jane Eyre was published before Wuthering Heights, it was not written until after Wuthering Heights was already completed; therefore, Jane Eyre may be read as Charlotte’s response to Emily’s solutions. Jane Eyre would be more detailed in discussing the specific aspects of English life that were suffering from the colonies’ negative influences, and by this closer exploration, Charlotte would arrive at a more complex understanding of the situation.

Sir Laurence Olivier is perhaps the most famous portrayal of Heathcliff which makes him much the romantic hero. Here he is with Merle Oberon, playing Cathy.

Charlotte’s juvenile works express the displacement of both the conquered and the conqueror when a colony is established. The conquerors are as displaced as the conquered because they are in a foreign land. Despite trying to recreate England in the colonies, the English never completely exterminated native cultures, and often, foreign cultures had influences on the English. Such influences caused many colonists to bring foreign ideas home with them to England. Unlike in Wuthering Heights where a foreigner destroys the local status quo, Jane Eyre reflects the belief that the English, from being influenced by the Other, could destroy England themselves. Charlotte portrays this idea in Jane Eyre by using images of blackness to show the breakdown of pure English culture; Charlotte believes the aspect of English life most affected by negative colonial influences is the relationship between English men and women.

Men went to the colonies more frequently than women, and men were the ones placed in positions of power over the natives. Such complete power is easily abused, especially when dealing with another race that might rebel. One way for the English to control the Other was by possessing their women. The lack of English women caused many Englishmen to seek another outlet for their sexual desires, and native women were the easiest solution. In fact, sexuality for the Englishman was probably enhanced by the mystery of being with a foreign woman (Azim 123). Throughout the colonies, it became an accepted practice for white planters to take female slaves as concubines; however, this resulted in a growing mulatto population that caused displacement for whites, natives, and mulattoes, making everyone’s place in the social structure uncertain; to ensure their own position, the whites rejected the mulattoes, and the natives, out of hatred for their conquerors, equally rejected those who were of half English blood (Meyer 252-3).

Charlotte Brontë believed this situation resulted in Englishmen going to the colonies because they could have more dominance over foreign women. Louis Moore contemplates going to the colonies for such a reason in Charlotte Brontë’s novel Shirley (570-71). Englishmen who oppressed foreign women then returned from the colonies believing they could also oppress Englishwomen (Meyer 260). In Jane Eyre, Charlotte Brontë depicts the oppression of Englishmen over their women by using foreign images, and particularly, the metaphor of the harem (Zonana 605-6).

Every household in Jane Eyre has colonial connections. These connections are not obvious with the Reed and Brocklehurst families, yet the two families are based on Yorkshire families whom the Brontës knew to have interests in the slave trade (Heywood 184). As a result of colonial influences, each English household in Jane Eyre resembles a harem (Zonana 605-6). Charlotte further illustrates the colonies’ negative influences by applying images of blackness to individual family members.

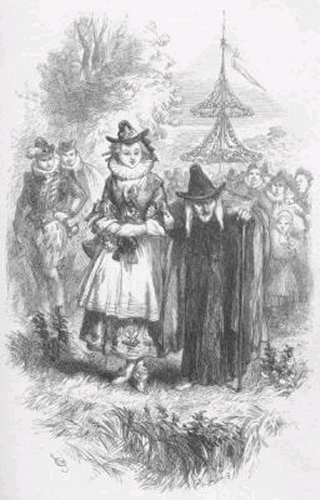

At Gateshead, John Reed, the only male in the house, is master over all the women. Because the Reed men have oppressed other races, it is in John’s blood to oppress, and he places his mother, sisters, and the servants in a position where they resemble his harem. The family’s colonial encounters are reflected in the blackness used to describe John and Mrs. Reed. John’s “thick lips” (83) are a metaphor for the way he is beginning to resemble a Negro because of his family’s contact with the African race (Meyer 260). Jane notices that John Reed reviled his mother “for her dark skin, similar to his own” (9). Later, when Jane visits her dying aunt, she sees Mrs. Reed’s “imperious, despotic eyebrow” (218), a sign of Mrs. Reed’s oppressive nature. Yet, Mrs. Reed is only despotic toward Jane. To John Reed, she is subservient, and she supports his detrimental behavior until he has destroyed his family’s fortune.

Jane is the only female in the Reed household who rebels against John’s sultanic tyranny. She tells him, “you are like a slave driver” (5) and says of herself, “like any other rebel slave, I felt resolved, in my desperation, to go all lengths” (6). When Jane defies Mrs. Reed, it is because by submitting to her son’s authority, her “chosen vassalage” (9), Mrs. Reed is contributing to the oppression of her fellow female. Mrs. Reed again submits to a man’s authority when Mr. Brocklehurst visits Gateshead. Brocklehurst expects and desires to hear negative stories of Jane, so Mrs. Reed tells degrading lies about Jane in an attempt to please him. Mrs. Reed does not even understand she is being unfair to Jane; instead, she feels she is doing her duty by obeying men. When Jane bursts out against her, Mrs. Reed thinks of Jane as of a different race (Meyer 249). She tells Jane, “you don’t understand these things: children must be corrected for their faults” (30) and “I assure you, I desire to be your friend” (30). In her own way, perhaps Mrs. Reed does have concern for Jane’s well-being; Mrs. Reed is much older than Jane, so she better understands the difficulties a woman experiences in a man’s world. She is warning Jane that rebellion against men will only cause Jane grief. However, Jane refuses to accept such a lifestyle, nor can she respect Mrs. Reed for submitting to it.

Jane goes away to school, thinking it will be an improvement over her life at Gateshead; however, Lowood school is also set up like a harem with Mr. Brocklehurst as its sultan. The Brocklehursts, like the Reeds, were also based on a slave trading Yorkshire family (Heywood 184); critics have not discussed the descriptions of blackness applied to Mr. Brocklehurst, yet I find they exist in the same way they were applied to the Reeds. When Brocklehurst appears at Gateshead, Jane describes him as a “black pillar” (24), having a “grim face at the top like a carved mask” (25) and “gray eyes” (25). Later when he whispers into Miss Temple’s ear, Jane fears to see the “dark orb” of Miss Temple’s eye turn toward her (54). Jane’s fear is that Mr. Brocklehurst will spread his blackness to Miss Temple, making her his slave, as he did to Mrs. Reed. Zonana argues that Brocklehurst’s sultanic quality is best reflected in his order that the girls at Lowood cut their hair to prevent vanity. Zonana sees vanity as the excuse Brocklehurst uses to strip the girls of their beauty and sexuality because if he cannot possess them, he wishes for no other men to find them attractive (608). Brocklehurst uses the Christian argument that vanity is a sin. Charlotte Brontë was well aware of how Christianity was often used as an excuse for British imperialism. Later in the novel, St. John will also use Christianity to further his own sultanic desires. Jane is as much a slave as the other women at Lowood; when Brocklehurst defames Jane before the school, she feels like a “slave or victim” (60). The only difference between Gateshead and Lowood is that the head woman in the harem, here Miss Temple rather than Mrs. Reed, although she tolerates the sultan, does not act as his tool to oppress her fellow women.

Thornfield also contains harem images because Mr. Rochester is connected to the colonies by his marriage to Bertha. Thornfield is the first harem type household where Jane is an adult, and consequently, more able to fight against the slave-like treatment of women. Thornfield is also the place where the harem image is most powerful, and Rochester is the man to whom the largest number of sultanic images are applied.

Rochester’s first appearance is when he falls from his horse and sprains his foot. Jane is unable to bring him his horse, so he remarks, “the mountain will never be brought to Mahomet, so all you can do is to aid Mahomet to go to the mountain” (106). Zonana argues that when Rochester compares himself to the Prophet Mahomet, he is displaying himself as “a polygamous, blasphemous despot—a sultan” (608). Rochester’s remark may appear as something anyone would say under such circumstances; however, Charlotte Brontë could simply have had him say, “Since the horse won’t come to me, can you help me to the horse.” Instead, she purposely used a phrase that conjures up the image of a sultan to foreshadow the later discovery of his marriage to Bertha. Furthermore, one hopes Charlotte would not let her characters speak clichés without a purpose.

Rochester is the Sultan of Thornfield by being master over a household of women. Even the female guests he invites to Thornfield appear submissive to him by Brontë’s use of Eastern images. Lady Ingram is described as having “inflated and darkened” features and a hard eye that reminds Jane of Mrs. Reed, and “A crimson velvet robe, and a shawl turban of some gold-wrought Indian fabric, invested her (I suppose she thought) with a truly imperial dignity” (161). The more important visitor to Thornfield is Blanche Ingram, Rochester’s intended future wife. Rochester remarks to Jane that Blanche is “A strapper—a real strapper, Jane: big, brown, and buxom; with hair just such as the ladies of Carthage must have had” (207). Jane also notices Blanche’s “dark and imperious eye” (174) and low brow, which liken Blanche to an inferior race in need of English male dominance (Meyer 260). The blackness attributed to the Ingram women might also suggest the family’s basis on a historical English family connected to the slave trade.

After Jane and Rochester fall in love, Rochester continues to be portrayed in ways depicting him as a master over women. Indeed, Jane is almost willing to be his slave as seen by her continually calling him “my master”. But there are moments when she revolts against his thinking of her as a member of his harem. At one point, Rochester comments of Jane, “I would not exchange this one little English girl for the Grand Turk’s whole seraglio—gazelle-eyes, houri forms, and all!” (255). Jane is annoyed with the Eastern allusion and says that neither she nor any woman should be treated like a slave. If Rochester goes to the bazaars looking for harem women, she says:

I’ll be preparing myself to go out as a missionary to preach liberty to them that are enslaved—your harem inmates among the rest. I’ll get admitted there, and I’ll stir up mutiny; and you, three-tailed bashaw as you are, sir, shall in a trice find yourself fettered amongst our hands: nor will I, for one, consent to cut your bonds till you have signed a charter, the most liberal that despot ever yet conferred (256).

During their next meeting, Rochester sings a song to Jane about an Indian woman dying with her husband. Jane responds, “he had talked of his future wife dying with him. What did he mean by such a pagan idea? I had no intention of dying with him—he might depend on that” (259).

However, Jane will soon realize how like a Sultan with multiple wives Rochester is. When he plans to marry her, he sets about having Thornfield cleaned although Jane remarks that she thinks the house is already clean enough. Jane does not realize that Rochester is trying to wipe out the blackness he has contracted from the colonies. However, what he actually needs to wipe out is his past marriage. Especially poignant to this scene is Grace Poole coming downstairs to supervise the cleaning. Grace, as the keeper of Bertha, knows just how filthy the house is, so she is best able to clean it (Meyer 264). However, no matter how clean the house is made, as long as Bertha is alive, she is Rochester’s lawful wife and cannot be wiped out.

Rochester, in marrying Jane, is willing to commit bigamy (or rather, polygamy like a sultan would do), but Mr. Mason stops the wedding by revealing the existence of Bertha. Rochester then brings Jane to see Bertha. It is a striking scene which Jane describes:

In the deep shade, at the farther end of the room, a figure ran backwards and forwards. What it was, whether beast or human being, one could not, at first sight tell; it grovelled, seemingly, on all fours; it snatched and growled like some strange wild animal; but it was covered with clothing, and a quantity of dark, grizzled hair, wild as a mane, hid its head and face (278).

Claudia Colteras as Bertha Mason Rochester in the 2006 BBC series of Jane Eyre. Note her dark skin suggests she is a mulatto – a threat to England’s whiteness.

Bertha is depicted as an animal on all fours, scarcely human, much as the English saw the natives of the lands they colonized as savage, scarcely human creatures. Women in harems were similarly treated as animals. Earlier, Jane had used the word seraglio to refer to a harem, yet Zonana points out that until the seventeenth century, a seraglio was also a place to keep wild beasts (600). Women who are kept in a seraglio or harem suffer enforced confinement, are undereducated, and kept inactive just like animals in cages (Zonana 602).

Bertha is doubly degraded by being depicted as a harem woman and an animal. Unlike the English women in the novel, Bertha is part animal because she is a Creole. Critics have argued that Brontë uses the term Creole to mean anyone born in the West Indies, not necessarily a mulatto (Meyer 253); however, Rochester says of Bertha’s mother, “Her mother, the Creole, was both a madwoman and a drunkard” (277). He then describes Bertha as having “red balls” for eyes (279). These red eyes are a sign of drunkenness, which presumably with her insanity, Bertha inherited from her mother. Insanity and drunkenness are both common racist stereotypes that the English associated with Africans to promote their belief in English superiority (Meyer 253-4). Therefore, Brontë appears to have intended that Bertha was a mulatto by the African blood she received from her mother.

Another racist belief of the time was that Africans were more closely related to apes than human beings; Charlotte Brontë’s unfinished novel Emma reflects this belief in the main character’s name, Matilda Fitzgibbon (Meyer 249). Fitz was often used as a prefix to show illegitimacy. A gibbon is a small tailless ape, resembling a monkey, meaning Matilda is the illegitimate offspring of a monkey (Meyer 249). In Jane Eyre, because Bertha is a Creole, she is half-human and half-animal (Meyer 250). As we saw in the above discussion of Wuthering Heights, Heathcliff being referred to as “it” may also suggest that his possible African origins liken him to an animal.

Rochester claims that Bertha’s insanity is inherited from her mother, but he may be trying to place blame, so he will not appear guilty for his wife’s mental instability. Bertha’s insanity could be the result of her displacement. Not only has she been displaced by having to leave her native country and come to England, but like Quashia, she is displaced from her family. Bertha’s case may even be more severe than Quashia’s, for although Quashia’s family was murdered, Bertha’s family directly helped cause her displacement by trying to change her identity so that Rochester would find her attractive. Bertha’s situation is a trap where she is betrayed by both her family and husband.

In Wide Sargasso Sea, Rochester assists in displacing Bertha by trying to make her Otherness familiar to him. In the novel, Bertha’s real name is Antoinette, but Rochester decides to call her Bertha because he says it is a name he has a fondness for (135). In response, Antoinette exclaims, “Bertha is not my name. You are trying to make me into someone else, calling me by another name” (147). By giving Antoinette an English name, Rochester is trying to Anglicize her so he can accept her. This is the same type of situation that occurs in Wuthering Heights when the Earnshaws give Heathcliff the name, and consequently, the identity of one of their deceased children. Spivak argues that such examples of name changes being applied to the Other by the conqueror represent how easily one’s identity can be determined by imperialism (250).

For Jane, the meeting with Bertha is startling because it is a type of colonial encounter with “the Other” (Azim 178). Since Rochester and Jane cannot marry, Rochester suggests they travel to another land where they can be together. Jane refuses because she fears becoming like Bertha, the Other. Without a legal marriage to Rochester, she may be treated as a harem woman or a mistress who can easily be cast off when he tires of her. By becoming Rochester’s mistress, Jane, like Bertha, would experience displacement from what she is accustomed to. Even if she could legally marry Rochester, Jane does not want to become Rochester’s slave by being financially dependent on him. Unlike in Wuthering Heights, eliminating the character representative of the Other will not provide a complete solution to the problem.

A poster for the 1939 film — Heathcliff looks more like the Frankenstein monster here than a romantic hero.

Jane leaves Thornfield to prevent her own transformation into the Other, yet after leaving, she almost succumbs to becoming like Bertha. Without a home, Jane suffers from hunger and at one point crawls on her hands and knees, just as Bertha does, until she is taken in by the Rivers family (Azim 179). The Rivers’ household is again set up like a harem, with St. John as the only man. Consequently, Jane again risks becoming a slave in a harem. When St. John proposes to Jane, he is asking that she become his wife and obey him. He also wants her to join him as a missionary in India. St. John uses Christianity to try to control Jane. Being a Christian, Jane finds his arguments difficult to resist, but she knows that going to India will cause her death. Despite St. John’s Christianity, Jane sees the despotic tendencies in his personality. By marrying St. John, not only will Jane become his slave, but she will be contributing to the oppression of others by preaching Christianity to the Indians so that they will submit to British imperialism. Since Jane fears displacement for herself, she realizes she cannot travel to India and displace or oppress others. Because Jane despised Mrs. Reed for trying to make her submissive to men when Mrs. Reed herself was already oppressed by them, Jane cannot now be a hypocrite; she wisely refuses St. John’s proposal.

Jane now returns to Thornfield and discovers Bertha has burnt down the house in her madness. However, Bertha may not be as mad as readers have long believed. Her burning of Thornfield may instead reflect the novel’s historical context. Slave revolts in the West Indies usually took place at night when plantation owners slept. Bertha’s escapes from her room are always at night. Night was the easiest time to rebel and catch the slave owners unprepared. Slaves would use fire to signal for an uprising among the other slaves, then destroy their masters’ property, and hopefully, kill their masters (Meyer 254-5). Bertha, as a Creole, is reenacting situations she may have experienced as a child in the West Indies. She is not only a madwoman, but a slave in revolt against the white man who oppresses her. Like Quashia in the juvenilia, Bertha is angry that her freedom, identity, and possessions have been taken from her. When Bertha burns Thornfield, Charlotte Brontë is not only speaking out against the oppression of the colonized, but she is also warning the English that they are bringing misfortune on themselves by colonizing and suppressing other races, just as the Duke of Wellington tried to make Quashia like him, and the Earnshaws tried to Anglicize Heathcliff. Colonization and suppression will only result in rebellion and destruction.

Meyer argues that Bertha does the great act of cleaning in the novel by burning down Thornfield. Rochester’s estate represents the wealth Rochester gained by his marriage to Bertha; by burning Thornfield, Bertha is making Rochester pay for his sins (Meyer 266), but at the same time, the destruction of his house and wife wipes away Rochester’s connection to the colonies. Rochester’s colonial background had caused his moral decline. After Thornfield burns, Rochester is left blind and lame, but Jane’s return to him brings light to destroy the blackness of his encounter with the Other, and Rochester regains his eyesight (Heywood 189).

With Jane and Rochester reunited, the novel seems like it should end happily. The loss of Rochester’s wealth is replaced by Jane’s inheritance from her uncle. Yet it is this inheritance that makes the conclusion of Jane Eyre so ambiguous. St. John learns that Jane is the heir to her uncle’s fortune when she writes her name in Indian ink (364). From a morocco pocketbook, St. John pulls out the letter stating Jane’s uncle has died and she has inherited his fortune (361). Both the Indian ink and the morocco pocketbook suggest a connection to the colonies (Meyer 267-8). Jane’s uncle was also in Madeira off the coast of Morocco, suggesting like the ink and pocketbook, that Mr. Eyre had a connection to the slave trade (Meyer 267). Therefore, even with Bertha’s death, Jane and Rochester are not free from a connection to the colonies. Instead, their financial stability is the result of slave trading. The complexity of this situation suggests Charlotte’s awareness that the British economy was now dependent upon its colonies. Emily’s solution that Britain separate itself from its colonies was not possible in Charlotte’s opinion.

At the time Charlotte was writing Jane Eyre, the British colonies in the West Indies had already begun to fail. Attention was now being turned toward India as a place of colonization, and this is reflected in St. John going to India as a missionary. Charlotte feared the same difficulties the British faced in the West Indies were now going to be experienced in India (Meyer 257). Jane’s refusal to go to India with St. John shows her refusal to support British imperialism by helping oppress other races. St. John does go to India with the intention to spread Christianity to the natives, but Christianity is also a way for England to oppress and Anglicize the Other (Azim 181). If St. John is helping the Indian natives, it is only how he wishes to help them. It is questionable just how St. John is helping the Indians by imposing Western religion on them. Perhaps he is more concerned with doing what he sees as his Christian duty rather than being truly Christian toward his Indian brothers.

Zonana reads the conclusion of Jane Eyre as Charlotte’s promotion of Christianity as a way to reform English men and prevent polygamy. Once England is redeemed from foreign influences, it can go forth and redeem other races (612). Zonana adds that Brontë is purposely overlooking the patriarchal oppression that is also part of Christianity to provide a solution (612). However, I believe Charlotte saw Christianity as part of the problem rather than the complete answer. By establishing colonies, Britain was responsible for beginning colonial problems. The British pretended to be doing their Christian duty by bringing the Other to the true religion, but Christian duty was merely being used as an excuse for the British to legitimize stealing land.

At the end of the novel, Jane says of St. John, “he labours for his race…he hews down like a giant the prejudices of creed and cast that encumber it” (433). But the race St. John labors for is not that of the Christians but of the English. The creed and cast that encumber it are not necessarily England’s prejudices against India, but very possibly India’s prejudices against England. With the breakdown of these, the English believe India will be more accepting of English ways. St. John is merely adding to the problem by trying to make the East resemble the West. Nor is this a successful labor. Being in India has made St. John ill, and Jane knows his death is fast approaching. His connection to the colonies, as has been the case for so many other Brontë characters, only causes his own downfall (Pell 405).

As St. John’s death approaches, Jane writes that he will go to “the joy of his Lord” (430). Why did Charlotte Brontë not write “the Lord”? Did she realize that the Christian God is not necessarily the God for India? Charlotte most likely felt Christianity was the true religion, but Jane Eyre’s argument is that the West should not try to control the East. By continually trying to make the Orient like the Occident before the Occident can be polluted by the Orient, England will be foolishly applying the problem as a solution. As a result, the problem will only increase. The closing words of the novel are St. John praying, “come, Lord Jesus” (433). These are Charlotte’s words as much as St. John’s. Charlotte is leaving the problem in the hands of God. She has pointed out the problem to the English. If England cannot see the wrongs of oppressing other races, perhaps they will stop the oppression for England’s own survival.

When Jane is bullied by John Reed, she exclaims to him, “you are like the Roman Emperors” (5). The comparison is significant because Britain was now an oppressive empire much like Rome had been. Charlotte knew that all great empires must eventually fall. In writing “come, Lord Jesus!”, Charlotte Brontë is asking God to awaken the English people to their situation before they bring destruction down upon themselves.

Emily Brontë died the year following the publication of Wuthering Heights and Jane Eyre. To my knowledge, there is no extant record of Emily’s reactions to Jane Eyre. Emily would never write another novel, so it would seem that Charlotte and Emily’s ongoing discussion of the subject came to an end with Emily’s death. However, six years later, Charlotte Brontë’s last novel, Villette, was published and the colonial theme was reintroduced. The theme is much weaker in Villette than in Jane Eyre or Wuthering Heights, yet the novel reflects Charlotte’s continuing interest in Britain’s colonial problems. Villette is a more mature Charlotte’s response to both Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights, and she incorporates ideas from both novels to arrive at yet another solution to the colonial situation.

Meyer is the first critic to notice the colonial theme in Villette, yet she only discusses it in regards to the conclusion of the novel. Meyer suggests that the storm which kills M. Paul is caused by the West Indians’ rage and desire for revenge over M. Paul who has been a slave master while in the West Indies (248). While Villette does state that M. Paul goes to the West Indies to take care of business there for a friend, the actual position M. Paul holds in the West Indies is never stated and M. Paul’s decease is extremely obscure. As Schaeffer points out, “The death of M. Paul at sea is not even mentioned, yet we know it occurred” (xiv). M. Paul’s death has been accepted by most critics as the interpretation of the novel’s conclusion. Neither does the text state where the storm occurred; it may have happened closer to English shores than near the West Indies. Meyer’s theory that the storm reflects the anger of the slaves whom M. Paul has been master over appears to have little textual basis.

However, by examining the entire novel rather than just the conclusion, I found that Charlotte does use several of the same colonial images that appeared in Jane Eyre. If M. Paul does have some connection to slavery, it might account for the black descriptions Charlotte uses to describe him. The first description of M. Paul is that he has a “black head” and “broad, sallow brow” (121). Later, his head has a “velvet blackness” (128), and there is a “blackness” of his cranium (297). These are just a few of several similar passages that suggest Charlotte was using the same black imagery she used in Jane Eyre. However, this argument is weakened by M. Paul being based on Charlotte’s own Belgian professor, M. Heger. Charlotte once described M. Heger as “a little black ugly being” (Gordon 94). M. Heger’s own dark complexion was the result of his Spanish origins, so the black descriptions applied to M. Paul may be the result of his basis on M. Heger rather than any connection to slavery.

Villette is also similar to Jane Eyre because the novel’s opening scene presents a harem type household. Graham is the only man, while his mother, Lucy, and Polly are all present to serve him. However, none of the other households in the novel appears to fit the harem pattern. Later in the novel, Graham wins a turban in a lottery at the opera. One day while he is sleeping, his mother jokingly places it on his head, claiming it makes him look Eastern, and she calls him “my lord” (261). The situations Graham is placed in may portray him as having a sultan’s position, yet his character does not suggest that he holds sultanic attitudes. Furthermore, it is strange that Graham would have sultanic qualities applied to him if M. Paul is the one intended to have the blackened connections to the colonies.

The concept of the Other also appears in the novel, only this time, it is the main character, Lucy, who is the Other because she is in a foreign land; M. Paul continually complains to her about the English who are the Other for him. Because Lucy is of a different race, M. Paul sees her as inferior to him, and at one point, he even calls her a “sauvage” (305). Meyer argues that because of the way M. Paul treats Lucy, it is best that he die because had he returned to marry Lucy, he would have treated her as his slave just as the men in Jane Eyre oppress their English women (248). However, it is questionable that Lucy would have submitted to such treatment. Jane Eyre admired St. John for his Christianity, but she did not let him use Christianity to control her. Lucy similarly admires M. Paul’s kind heart, at one point calling him “my Christian hero” (382), and later when he sets up the school for her, he is “my king; royal for me had been that hand’s bounty; to offer homage was both a joy and a duty” (467). However, like Jane Eyre, Lucy does not always willingly submit to a man; M. Paul tries to convert Lucy to Catholicism, but she refuses to give up her own identity. In trying to convert Lucy, M. Paul is trying to make the Other familiar to him, much as applying English names to Heathcliff and Bertha were used in Wuthering Heights and Wide Sargasso Sea. Like Jane who refuses to become the Other, Lucy refuses to change her identity. But even with this concept of the Other applied to Lucy, there is no connection to the colonies in these scenes.

Meyer’s theory for Villette’s containing the colonial theme rests on the death of M. Paul occurring because of his connections to slavery in the colonies. I do not find these arguments convincing, but if Meyer is correct, perhaps Villette could be seen as Charlotte agreeing with Emily. Emily’s solution was to end contact with the Other, represented by the death of Heathcliff and the return to the original status quo. Perhaps Charlotte now saw Jane’s ability to reform Rochester from his sultanic qualities as unrealistic. Instead, Charlotte may now be agreeing with Emily that contact with the Other must end. But Charlotte goes a step further than Emily. Rather than destroying the Other, Villette suggests that once men have been defiled by their contact with the colonies, they cannot be reformed, so women must resist having relationships with them. Such resistance on the part of women would also save England by preventing the regeneration of oppressive men in future generations just as the regeneration of oppressors is prevented in Wuthering Heights by the death of Heathcliff. As Jane Eyre showed, a total breach with the colonies was not economically possible, so Villette offers a solution that allows each woman to solve the problem for herself. Lucy may end up alone at the novel’s conclusion, but to be alone is preferable to being oppressed by a despotic man. I am hesitant to believe that M. Paul is connected to the slave trade as Meyer argues, yet the concept of the Other in Villette might still suggest that Charlotte had a further solution to the problem of Britain’s colonies.

The issue of the colonies appears in Charlotte’s juvenilia as well as her novels, Jane Eyre and Villette, and in Emily’s novel, Wuthering Heights. Although the theme appears in Charlotte’s work more than in that of Emily, by looking at the order in which the texts were written, it is possible to see Charlotte and Emily using their writings as a way to discuss England’s colonial problems between themselves. By reacting to each other’s ideas, Charlotte and Emily Brontë together explored their fear that England’s colonies would destroy its national identity and bring moral ruin to the English people. Each Brontë work seeks a solution to the problem and builds on the text prior to it. Although it is questionable which Brontë text provides the best solution, looking at the chronological order of the texts and the way they build upon each other helps us better understand how the Brontë sisters collaborated to form some of the finest novels in British literature.

Works Cited

Azim, Firdous. The Colonial Rise of the Novel. London: Routledge, 1993.

Brontë, Charlotte. Jane Eyre. 1847. New York: Bantam, 1986.

Brontë, Charlotte. Shirley. 1849. New York: Penguin, 1985.

Brontë, Charlotte. Villette. 1853. New York: Bantam, 1986.

Brontë, Emily. Wuthering Heights. 1847. Bantam, 1983.

Heywood, Christopher. “Yorkshire Slavery in Wuthering Heights.” Review of English Studies 38 (1987): 184-98.

Gordon, Lyndall. Charlotte Brontë: A Passionate Life. New York: W.W. Norton, 1995.

Meyer, Susan L. “Colonialism and the Figurative Strategy of Jane Eyre.” Victorian Studies 33 (1990): 247-68.

Pell, Nancy. “Resistance, Rebellion, and Marriage: The Economics of Jane Eyre.” Nineteenth Century Fiction 31 (1977): 397-420.

Ratchford, Fannie Elizabeth. The Brontës’ Web of Childhood. New York: Russell and Russell, 1964.

Rhys, Jean. Wide Sargasso Sea. 1966. New York: W.W. Norton, 1982.

Schaeffer, Susan Fromberg. “‘The Sharp Lesson of Experience’: Charlotte Brontë’s Villette.” Villette. 1853. By Charlotte Brontë. New York: Bantam, 1986.

Spivak, Gaytri C. “Three Women’s Texts and a Critique of Imperialism.” Critical Inquiry 12 (1985): 243-61.

Zonana, Joyce. “The Sultan and the Slave: Feminist Orientalism and the Structure of Jane Eyre.” Signs 18 (1993): 592-617.

__________________________________________________

Tyler Tichelaar, Ph.D., is the author of The Children of Arthur series, beginning with Arthur’s Legacy and including Lilith’s Love which is largely a sequel to Dracula. His scholarly nonfiction works include King Arthur’s Children: A Study in Fiction and Tradition and The Gothic Wanderer: From Transgression to Redemption. You can learn more about him at www.GothicWanderer.com and www.ChildrenofArthur.com.